Why the fun lies in the middle

The hidden privilege of having neither too little nor too much

“Give me neither poverty nor riches, but give me only my daily bread.

Otherwise, I may have too much and disown you and say, ‘Who is the Lord?’

Or I may become poor and steal, and so dishonor the name of my God.”

— Proverbs 30:8–9

You’ve probably heard the phrase “the squeezed middle.” Middle-class families often feature in gloomy headlines—caught in the crossfire of policy changes. Private education? Subject to VAT. Buy-to-let landlords? Hit with a 5% surcharge. Support? Too rich for benefits, too poor for privileges. From many angles, the middle does look squeezed.

But I want to offer a different perspective: the middle may also be where the fun lies.

Recently at work, I’ve been helping my team think through gamification strategies. And in doing so, I revisited a deceptively simple question: What makes something fun to play? One classic definition by Salen and Zimmerman puts it like this: “A game is a system in which players engage in an artificial conflict, defined by rules, that results in a quantifiable outcome.” In other words, games are structured struggles. Without constraints and uncertainty, there’s no meaningful challenge. Without meaningful challenge, there’s no satisfaction. Games are only fun when you’re just powerful enough to try—but not so powerful you can skip the trying altogether.

And the same, I think, goes for the middle class. The middle class is perfectly designed for the game of life.

The kitchen that taught me constraint

A month ago, we started planning a kitchen renovation. When we bought the house, we inherited an 18-year-old kitchen. It was functional, sure, but tired. I had dreams—extension dreams. Pinterest-worthy dreams. But soon I realised that a side return would cost more than our entire renovation budget, even before VAT. So, I let it go.

Instead of expanding, I challenged myself to work within the existing footprint. No walls were knocked down. Instead, I bought the Handbook of Interior Design and determined to achieve great effects by leaning on design tricks and layout tweaks alone. I spent weeks sketching about how to move cabniets, fridge, to make the space work and exchanged 10+ emails with 3 kitchen designers... It became a puzzle: what can I change by sticking to the original floorplan?

And here’s the strange part: I loved it.

There was joy in the trade-offs. Joy in weighing options, reading reviews, calling friends for tips. I felt alert and alive. It reminded me of how I used to feel solving bonus maths problems as a child—stuck but excited, frustrated but intrigued.

Had I been wealthier, I might’ve just bulldozed and rebuilt (or more likely buy a turnkey mansion directly). Had I been less secure, I might not have had the option to renovate at all. But here, in the middle, I got to play.

A child’s pop-up toy and adult limitations

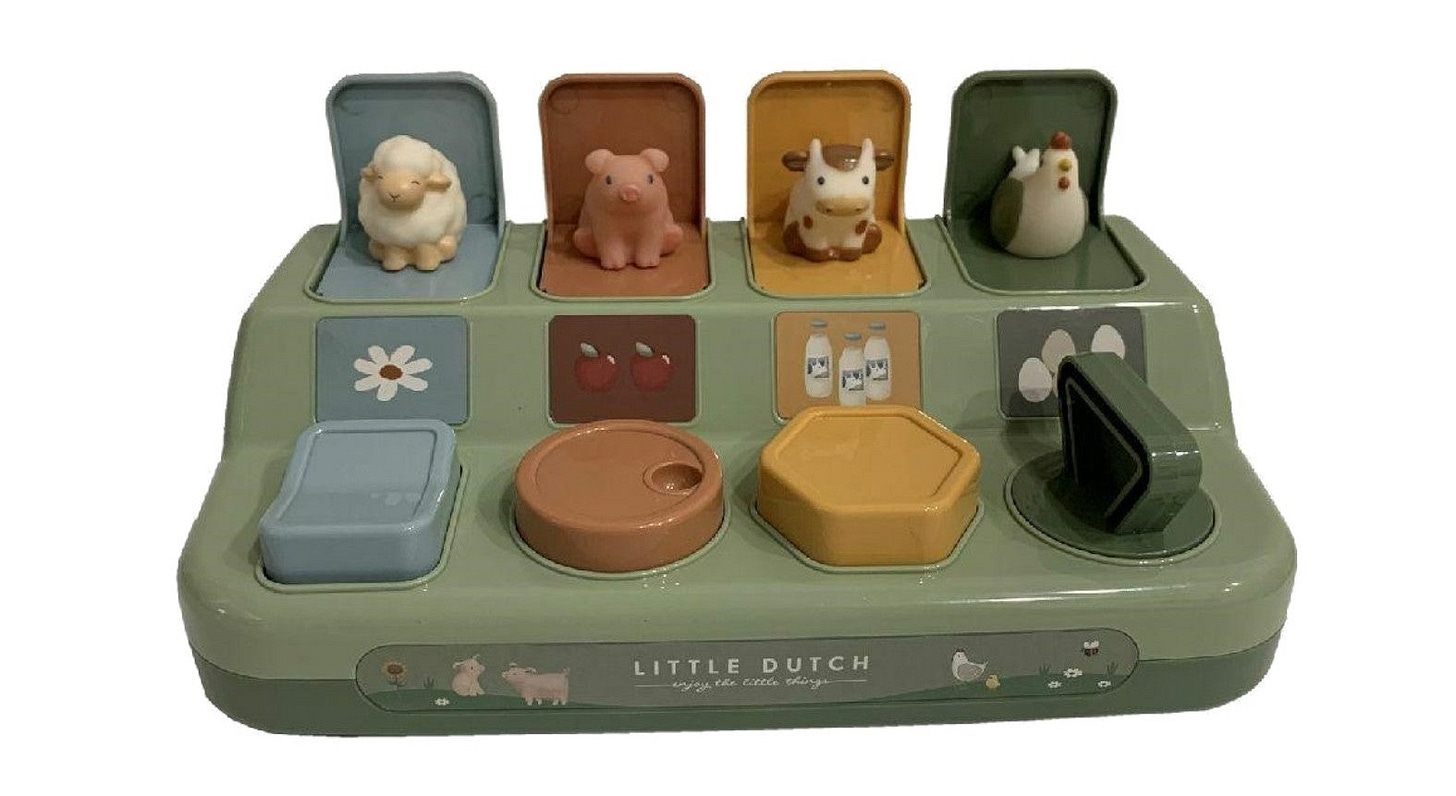

Watching my 1-year-old son play with his pop-up toy, I’m reminded again of how fun arises from the right level of difficulty. He pushes, twists, pulls, and every “pop” brings delight. But if I play with it, it bores me in seconds—I can “win” without effort.

He’s at that perfect age where the toy matches his abilities. Just hard enough to entertain. Just easy enough to feel mastery.

As adults, we outgrow the pop-up toy. But we still crave the feeling—that balance of challenge and agency. The middle class, in many ways, is where that balance lives. We don’t have unlimited money, but we have some. We can’t bend the rules, but we get to play by them.

Why rule-bending isn’t fun

The very wealthy might renovate with ease, travel without limits, outsource every frustration. But doesn’t that begin to feel like playing chess with all queens? Powerful, but boring. A game without constraints is a sandbox—not a game.

The very poor, on the other hand, may not feel themselves to be in the game. They’re grinding, not playing.

Only in the middle do we get to experiment, reflect, stretch a little past comfort. We make decisions. We learn. We feel the progress.

Exhortation from the middle

Of course, I may be romanticising it. I haven’t lived as a billionaire. Perhaps their games are different—legacy, politics, inner peace. But I wonder if even they, in quiet moments, long for rules they can’t bend. For a little bit of friction. For a game where not everything is guaranteed.

That’s what I want to remember—for myself, and one day for my son.

Because if we design life like a good game, we don’t need infinite power or wealth. We just need enough to play meaningfully.

So here’s my middle-class pledge:

To stay alert in trade-offs.

To resist shortcuts.

To cherish challenges.

To remodel my life like my kitchen:

with creativity, not carte blanche.

The middle may be squeezed—but oh, what a game it gives us to play.